U.S. Life Saving Station 30 is one of the few remaining facilities of its type in the United States.

By Donald Wittkowski

They lived by a creed that underscored the importance and dangers of their job: “You have to go out, but you don’t have to come back.”

Risking their lives to save others, the “surf men” who toiled at the U.S. Life-Saving Station 30 faced possible serious injury or death each time they rushed out to rescue shipwreck survivors off the Ocean City coast.

“When you show up at a wreck, you have to do everything possible to save people on that wreck. There are no ifs, ands or buts about it,” local historian John Loeper explained of the responsibilities of the surf men.

More than 100 years after the men stopped working at the Life-Saving Station 30 in Ocean City, Loeper believes it is time that each one of them should be recognized for their sacrifices and heroism.

The station, located at Fourth Street and Atlantic Avenue, formally opened to the public as a museum last year to showcase Ocean City’s history with the U.S. Life-Saving Service, the forerunner to the U.S. Coast Guard.

Hoping to distill history down on a more personal level, Loeper and others are trying to build dossiers on all of the men who worked at the station from 1872 to 1915 – in effect, bringing them back to life so that museum visitors will understand exactly what they did long ago.

“If we get dossiers on all of these guys, then we can talk about them and give them credit,” said Loeper, who serves as the museum chairman.

By Donald Wittkowski

They lived by a creed that underscored the importance and dangers of their job: “You have to go out, but you don’t have to come back.”

Risking their lives to save others, the “surf men” who toiled at the U.S. Life-Saving Station 30 faced possible serious injury or death each time they rushed out to rescue shipwreck survivors off the Ocean City coast.

“When you show up at a wreck, you have to do everything possible to save people on that wreck. There are no ifs, ands or buts about it,” local historian John Loeper explained of the responsibilities of the surf men.

More than 100 years after the men stopped working at the Life-Saving Station 30 in Ocean City, Loeper believes it is time that each one of them should be recognized for their sacrifices and heroism.

The station, located at Fourth Street and Atlantic Avenue, formally opened to the public as a museum last year to showcase Ocean City’s history with the U.S. Life-Saving Service, the forerunner to the U.S. Coast Guard.

Hoping to distill history down on a more personal level, Loeper and others are trying to build dossiers on all of the men who worked at the station from 1872 to 1915 – in effect, bringing them back to life so that museum visitors will understand exactly what they did long ago.

“If we get dossiers on all of these guys, then we can talk about them and give them credit,” said Loeper, who serves as the museum chairman.

Dating to the late 1800s, the U.S. Life-Saving Station has been converted into a museum.

The museum has compiled a list of 62 surf men, including four of the “keepers” who were in charge of the station. In conducting their research, museum officials have located the gravesites of 30 of the men. They are determined to learn more about each man, Loeper noted.

“When you go down the list, you see some familiar South Jersey names,” he said.

For instance, Loeper believes that a surf man named Charles P. Leek may be related to the storied Leek boatbuilding family of South Jersey.

It was discovered that another man on the list, named William J. Chadwick, was a relative of present-day Ocean City architect James Chadwick, Loeper said.

“When you look at these guys on the list, these names run through the history of South Jersey,” he said.

Museum officials have been researching the Life-Saving Station’s old documents, U.S. Census records and other archival information to learn more about each man.

Now, they are also reaching out to the public through the news media in hopes that will bring them even more information about the surf men, perhaps from a relative or someone else with local ties.

“Every once in a while, someone will come through the station and say, ‘Oh, that looks like a relative of ours,”’ Loeper said.

Dating to the late 1800s, the U.S. Life-Saving Station has been converted into a museum.

The museum has compiled a list of 62 surf men, including four of the “keepers” who were in charge of the station. In conducting their research, museum officials have located the gravesites of 30 of the men. They are determined to learn more about each man, Loeper noted.

“When you go down the list, you see some familiar South Jersey names,” he said.

For instance, Loeper believes that a surf man named Charles P. Leek may be related to the storied Leek boatbuilding family of South Jersey.

It was discovered that another man on the list, named William J. Chadwick, was a relative of present-day Ocean City architect James Chadwick, Loeper said.

“When you look at these guys on the list, these names run through the history of South Jersey,” he said.

Museum officials have been researching the Life-Saving Station’s old documents, U.S. Census records and other archival information to learn more about each man.

Now, they are also reaching out to the public through the news media in hopes that will bring them even more information about the surf men, perhaps from a relative or someone else with local ties.

“Every once in a while, someone will come through the station and say, ‘Oh, that looks like a relative of ours,”’ Loeper said.

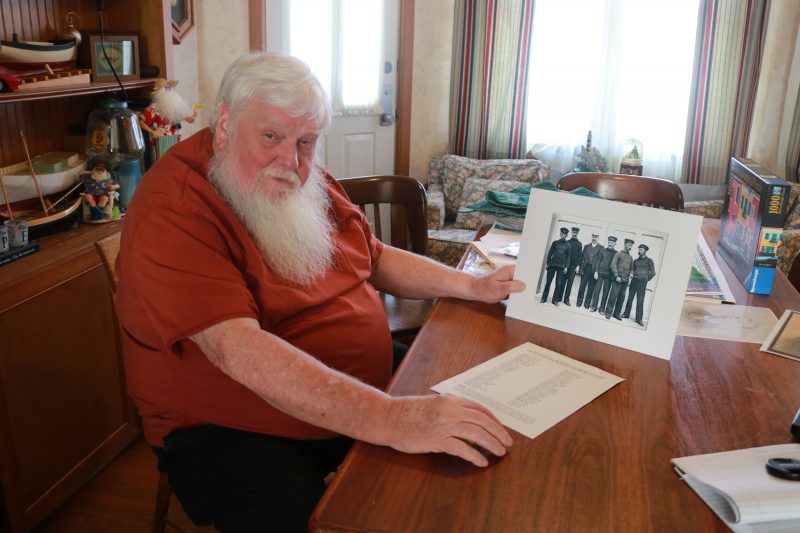

John Loeper, chairman of the U.S. Life-Saving Station 30, displays an old photo of the Ocean City surf men who responded to the Sindia shipwreck in 1901.

Brimming with artifacts from the U.S. Life-Saving Service days, the museum also features old black-and-white photographs of some of the surf men. The photos show wiry, mustachioed men in dark clothing.

“It was a pretty rigorous life to do this,” Loeper said. “There were very few fat life-saving guys.”

The surf men earned $40 per month, a relatively handsome wage in their day, Loeper noted. The Life-Saving Station Museum includes a dormitory where the men would sleep. The keeper had his separate living quarters, reflecting his status as the man in charge.

When needed, the surf men would rush to the rescue of distressed or sinking ships. If one was spotted close to shore, they would frantically take action, either launching their lifeboats or deploying a rope-operated system to save the ship passengers.

“These guys were every bit as valuable as Civil War soldiers,” Loeper said. “There were just a few of them working in the station, but they would do a monumental job of saving people in severe conditions.”

John Loeper, chairman of the U.S. Life-Saving Station 30, displays an old photo of the Ocean City surf men who responded to the Sindia shipwreck in 1901.

Brimming with artifacts from the U.S. Life-Saving Service days, the museum also features old black-and-white photographs of some of the surf men. The photos show wiry, mustachioed men in dark clothing.

“It was a pretty rigorous life to do this,” Loeper said. “There were very few fat life-saving guys.”

The surf men earned $40 per month, a relatively handsome wage in their day, Loeper noted. The Life-Saving Station Museum includes a dormitory where the men would sleep. The keeper had his separate living quarters, reflecting his status as the man in charge.

When needed, the surf men would rush to the rescue of distressed or sinking ships. If one was spotted close to shore, they would frantically take action, either launching their lifeboats or deploying a rope-operated system to save the ship passengers.

“These guys were every bit as valuable as Civil War soldiers,” Loeper said. “There were just a few of them working in the station, but they would do a monumental job of saving people in severe conditions.”

This beach cart in the museum was used in the rescue of passengers of shipwrecks and other emergencies at the turn of the century.

As ship travel expanded in the early 19th century, the government made passenger safety a higher priority. The U.S. Life-Saving Service, a government agency, was formed in 1848 to rescue shipwrecked passengers and crew members. It was the predecessor to the U.S. Coast Guard, which was created in 1915.

Ocean City’s station was occupied by the Life-Saving Service until 1915. The Coast Guard took over then and continued to use it for life-saving operations until the 1940s. It was then sold to private owners and became a residence. A succession of owners had it as their private home for decades before the city acquired it in 2010, beginning the process for the building’s conversion into a museum.

Loeper pointed out that the surf men lived by the inviolable code, “You have to go out, but you don’t have to come back.”

“This is what they lived by. This is what they woke up to every morning. This is why it is so important for people to know what they did,” he said of the museum’s plan to recognize and honor all of the surf men.

Following is an alphabetical list of the 62 surf men. The keepers’ names are in boldface:

George H. Adams, Edward Armstrong, Joseph E. Bauer, Christopher Bentham, Leroy Bentham,

This beach cart in the museum was used in the rescue of passengers of shipwrecks and other emergencies at the turn of the century.

As ship travel expanded in the early 19th century, the government made passenger safety a higher priority. The U.S. Life-Saving Service, a government agency, was formed in 1848 to rescue shipwrecked passengers and crew members. It was the predecessor to the U.S. Coast Guard, which was created in 1915.

Ocean City’s station was occupied by the Life-Saving Service until 1915. The Coast Guard took over then and continued to use it for life-saving operations until the 1940s. It was then sold to private owners and became a residence. A succession of owners had it as their private home for decades before the city acquired it in 2010, beginning the process for the building’s conversion into a museum.

Loeper pointed out that the surf men lived by the inviolable code, “You have to go out, but you don’t have to come back.”

“This is what they lived by. This is what they woke up to every morning. This is why it is so important for people to know what they did,” he said of the museum’s plan to recognize and honor all of the surf men.

Following is an alphabetical list of the 62 surf men. The keepers’ names are in boldface:

George H. Adams, Edward Armstrong, Joseph E. Bauer, Christopher Bentham, Leroy Bentham,  The tiny "watch tower" on the roof allowed the surf men to search the ocean for shipwrecks.

The tiny "watch tower" on the roof allowed the surf men to search the ocean for shipwrecks.