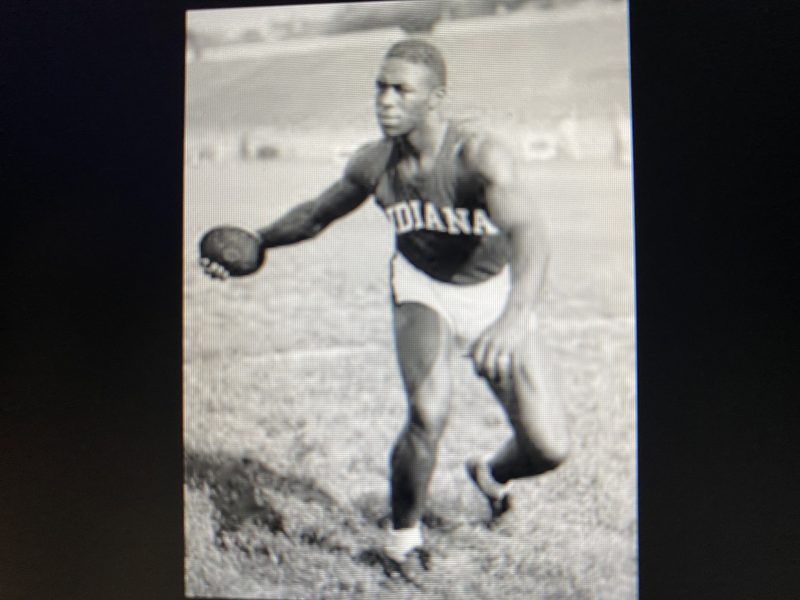

Archie Harris during his days as a world-class discus thrower at Indiana University. (Photo courtesy of Indiana University Track and Field)

By TIM KELLY

You might think you know Ocean City history, but do you know about “Widow’s Row?” Do you know about Archie Haggie Harris, Jr.? How about Turner’s Pool Hall?

We didn’t either.

They are all part of Ocean City’s rich African American heritage, but one largely unknown in a town that otherwise embraces and celebrates its past.

“We have a very significant black history in Ocean City,” said local historian Loretta Thompson Harris. “Unfortunately, it is not very well documented.”

Harris, a fourth generation Ocean City Thompson family member, presented a fascinating look at the people, businesses and contributions of the African American community at Friday’s meeting of Ocean City AARP Chapter 1062 at the Ocean City Free Public Library.

Her talk, a tour de force spanning the earliest days of black settlement here to present day, revealed many interesting facts heretofore unknown by most Ocean City residents and visitors, even the local black community itself.

“Many families haven’t passed down their histories,” she said. “That’s mainly because they don’t know their own background.”

That is changing, she said, with the advent of DNA testing and renewed interest in preserving history before it fades away forever.

Harris is helping to lead the effort. Since retiring from her business career – she was an executive with Atlantic City Electric for more than 30 years – Harris painstakingly drew up charts showing the family trees of African American families, combed through dusty newspaper libraries and public records files, and trudged through cemeteries in her quest to document local black history.

By TIM KELLY

You might think you know Ocean City history, but do you know about “Widow’s Row?” Do you know about Archie Haggie Harris, Jr.? How about Turner’s Pool Hall?

We didn’t either.

They are all part of Ocean City’s rich African American heritage, but one largely unknown in a town that otherwise embraces and celebrates its past.

“We have a very significant black history in Ocean City,” said local historian Loretta Thompson Harris. “Unfortunately, it is not very well documented.”

Harris, a fourth generation Ocean City Thompson family member, presented a fascinating look at the people, businesses and contributions of the African American community at Friday’s meeting of Ocean City AARP Chapter 1062 at the Ocean City Free Public Library.

Her talk, a tour de force spanning the earliest days of black settlement here to present day, revealed many interesting facts heretofore unknown by most Ocean City residents and visitors, even the local black community itself.

“Many families haven’t passed down their histories,” she said. “That’s mainly because they don’t know their own background.”

That is changing, she said, with the advent of DNA testing and renewed interest in preserving history before it fades away forever.

Harris is helping to lead the effort. Since retiring from her business career – she was an executive with Atlantic City Electric for more than 30 years – Harris painstakingly drew up charts showing the family trees of African American families, combed through dusty newspaper libraries and public records files, and trudged through cemeteries in her quest to document local black history.

“Widow’s Row,” one of the earliest examples of Westside housing, as it appears today.

What the early homes lacked in aesthetics on the outside, they made up for on the inside “with love, community, compassion for each other and support of family,” Harris said. “That’s what I remember most about it.”

One of the earliest neighborhoods was a strip of 11 rowhomes on the 600 block of Haven Avenue, known as “Widow’s Row,” so-called because most of the households were headed by women whose husbands had passed on.

The two-story houses, about 16 feet wide each, had outhouses and no indoor plumbing. Over the years, the homes were upgraded, although two of the houses at the south end of the strip were demolished and replaced with a large three-story single family home.

“The Widow’s Row houses were pretty hard hit by Superstorm Sandy,” Harris said, but most of the remaining nine homes have been upgraded and remodeled and are still flourishing to this day.

Westside residents made their mark in educational, religious, and business circles, as well as city services, recreation, and just about every other walk of life.

Perhaps the most impressive, yet still lesser known personalities, was Archie Haggie Harris Jr. (no relation to Loretta Harris), arguably the greatest athlete to ever come out of Ocean City High School.

A star fullback on the football team, Harris’ prowess in track and field landed him at Indiana University on an athletic scholarship following his 1937 graduation. He fell just inches shy of making the 1936 U.S. Olympic team in the discus and the shot put, and went on to win Big 10 and national collegiate championships in both events at Indiana, where he held the world discus record in the 40s.

“Widow’s Row,” one of the earliest examples of Westside housing, as it appears today.

What the early homes lacked in aesthetics on the outside, they made up for on the inside “with love, community, compassion for each other and support of family,” Harris said. “That’s what I remember most about it.”

One of the earliest neighborhoods was a strip of 11 rowhomes on the 600 block of Haven Avenue, known as “Widow’s Row,” so-called because most of the households were headed by women whose husbands had passed on.

The two-story houses, about 16 feet wide each, had outhouses and no indoor plumbing. Over the years, the homes were upgraded, although two of the houses at the south end of the strip were demolished and replaced with a large three-story single family home.

“The Widow’s Row houses were pretty hard hit by Superstorm Sandy,” Harris said, but most of the remaining nine homes have been upgraded and remodeled and are still flourishing to this day.

Westside residents made their mark in educational, religious, and business circles, as well as city services, recreation, and just about every other walk of life.

Perhaps the most impressive, yet still lesser known personalities, was Archie Haggie Harris Jr. (no relation to Loretta Harris), arguably the greatest athlete to ever come out of Ocean City High School.

A star fullback on the football team, Harris’ prowess in track and field landed him at Indiana University on an athletic scholarship following his 1937 graduation. He fell just inches shy of making the 1936 U.S. Olympic team in the discus and the shot put, and went on to win Big 10 and national collegiate championships in both events at Indiana, where he held the world discus record in the 40s.

Archie Harris during his days as a world-class discus thrower at Indiana University. (Photo courtesy of Indiana University Track and Field)

“He would have gone to the Olympics, but then World War II intervened,” Loretta Harris said.

The war forced the cancellation of the planned 1940 Games scheduled for Tokyo and the 1944 Olympiad planned for London.

Instead, Archie Harris joined the Army Air Force, achieved the rank of Second Lieutenant and earned his wings as a fighter pilot of the 332nd Fighter Group – the famed Tuskegee Airmen.

When he returned home, Harris worked for the city and became one of the first black members of the Ocean City Police Department.

Archie Harris was named to the Ocean City Hall of Fame in 1993, or 56 years after his graduation and 28 years following his death. He was just 47 when he passed away in October of 1965, and was buried with full military honors in the Beverly National Cemetery in Burlington County.

Loretta Harris’ great grandfather arrived “in 1900 or 1901,” she said, starting a dynasty that is currently in its fifth Ocean City generation.

She enjoys documenting the town’s black history, even though it is becoming more time-consuming as she uncovers more information, and she is working on a book about African Americans to come out of Ocean City.

Harris said she would like to continue her work, but can’t do it all herself. She asked that anyone interested in helping to expand her research to contact her at 609-602-2151.

Archie Harris during his days as a world-class discus thrower at Indiana University. (Photo courtesy of Indiana University Track and Field)

“He would have gone to the Olympics, but then World War II intervened,” Loretta Harris said.

The war forced the cancellation of the planned 1940 Games scheduled for Tokyo and the 1944 Olympiad planned for London.

Instead, Archie Harris joined the Army Air Force, achieved the rank of Second Lieutenant and earned his wings as a fighter pilot of the 332nd Fighter Group – the famed Tuskegee Airmen.

When he returned home, Harris worked for the city and became one of the first black members of the Ocean City Police Department.

Archie Harris was named to the Ocean City Hall of Fame in 1993, or 56 years after his graduation and 28 years following his death. He was just 47 when he passed away in October of 1965, and was buried with full military honors in the Beverly National Cemetery in Burlington County.

Loretta Harris’ great grandfather arrived “in 1900 or 1901,” she said, starting a dynasty that is currently in its fifth Ocean City generation.

She enjoys documenting the town’s black history, even though it is becoming more time-consuming as she uncovers more information, and she is working on a book about African Americans to come out of Ocean City.

Harris said she would like to continue her work, but can’t do it all herself. She asked that anyone interested in helping to expand her research to contact her at 609-602-2151.